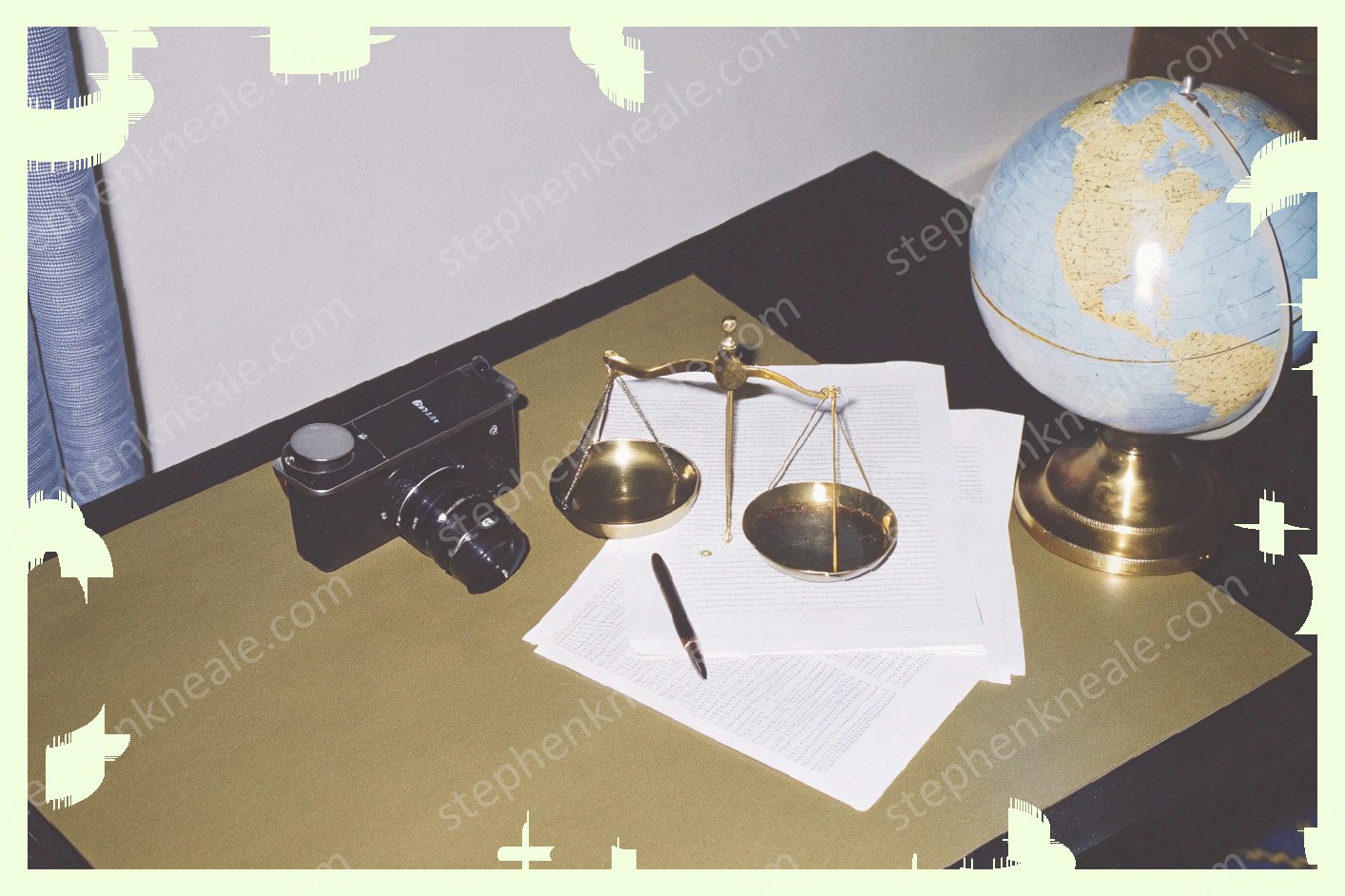

What is a Photography Usage Rights Agreement?

A photography usage rights agreement is a contract between a photographer or creative agency and a client that defines how the company can utilize a photographer’s images. This agreement is important for both the photographer and the client because it sets clear expectations for the use of the firm’s images and also protects the photographer’s rights.

A typical photography Usage Rights And License Agreement contains these basic elements: Grants – The terms under which the photographer will allow the client to use its images, such as the permission to modify or create derivative works using the images, whether the use will be exclusive or nonexclusive , and the territory in which the work will be used. Term – The duration of the photographer’s rights granted to the client and starting point of use by the client. Royalty – The consideration paid to the photographer for granting these rights; the compensation can be upfront or based on subsequent use by the client of the photographer’s image. Clients often pay royalties on a "per unit" basis — a single license for each individual use of the image or a "run"-based license, which entitles the client to reprint the images a set amount of times. A license can also occur on a one-time basis or for a certain period, such as a year or two years. Credit – Whether the photographer is entitled to credit for its work as part of an agreement with the client.

Provisions to Include in a Photography Agreement

Photos are indispensable marketing tools for almost all businesses. The most common way that companies will obtain photos is by hiring outside photographers or photography services to fulfill the needs. As such, a company will need a photography usage rights agreement to ensure that there is a clear understanding and description of the scope of the rights that are being conveyed to it.

Duration. Clause i. This term helps to set expectations as to when the company may begin to use the photos. The end date for the photography usage rights can either be set to last for a specific duration or the end date can be tied to an event, such as the first date of publication of the photos, the date the photos are uploaded online or the date of the first broadcast or other usage of the photos.

Exclusivity. Clause ii. An exclusivity term grants a company priority rights to the photos, meaning that the photographer may be restricted from licensing or selling the photos to others for a certain time period or for a particular type of use.

Territories. Clause iii. The largest territory for which a company should be able to obtain photos from a photographer would be a worldwide license, but at a minimum the territory should be set to the location of the company’s business and where related products or services are offered or perceived to be offered. For a local business, it probably makes the most sense to limit the territory to a specific city or region, as this may not only impact where the photos can be used, but it may also impact the compensation package. Having a worldwide territory may also limit the compensation options or may reduce the compensation for the photos. Depending on the nature of the business, having a limited territory may be all that is necessary.

Types of Use. Clause iv. It is important to limit the types of use origination companies can have for the photos. Otherwise, the photographer might be able to claim that a use is authorized, even if it is outside the contemplated use (e.g. a wedding photographer using wedding photos on the cover of a magazine). Also, it is equally important to ensure that a photographer knows how photos can not be used, as it has been our experience that it can be arguably more important for a photographer to know what is prohibited than what is authorized.

How to Write a Comprehensive and Effective Agreement

The first thing to keep in mind when drafting a photography usage rights agreement is to be as specific as possible and detailed as necessary. Also, again, be as clear as possible, for both you and the client. When you are deciding on file format – which can be high-res Tiff files, raw format files, or black and white tiff files for instance, make sure it is acceptable to the client, but also protect yourself in the agreement. Maybe the types of files you provide to them, is what you agree to and they cannot use any of your other files for the photoshoot. Again this can go both ways, the client can ask that they receive all of the files regardless of type, but if you do not want to provide them all, you are within your rights, until it has been agreed to otherwise and you have a binding contract.

Things To Avoid

Many mistakes can be avoided with proper planning, understanding and negotiation . The following is a "shopping list" of common mistakes made when entering into a photography usage rights agreement:

Failing to address timing of payment in the usage agreement and delaying payment of any or all amounts owed

Failing to explore how to maximize the seller’s exposure through editorial use of the photographs or otherwise

Entering into an agreement with a non-exclusive grant of rights, particularly if there is an exclusive rights-granting agreement in place with a different party or parties

Failing to review the entire chain of title to make sure no issues exist with granting rights to the seller

Failing to get full rights to all photographs for which there may have been licensed or sponsored third-party rights claiming to use those photographs

Failing to disclose whether an identified "look and feel" in an ad or campaign was created by the seller or by some third party(s) and, if the latter, what rights the seller may have to use that "look and feel" as it relates to the photographs

Failing to disclose whether certain locations to be used in an ad or campaign have been previously photographed, which could infringe the rights of a third party and/or serve as a basis for creating a parody or taste issue (which could erode consumer confidence in the ad or campaign)

Failing to properly review the components of the "look and feel" being granted in order to make sure that all rights are being granted and the seller has full rights to an unlimited use of the end product in all media

Failing to disclose whether a photo cannot be used in certain media by contract restrictions or other limitations

Failing to address how certain images may be perceived by consumers

Failing to address unknown actors or rights holders

Failing to address the proper scope of print publication, including foreign language editions

Providing a broad grant of rights when only certain, enumerated rights may be needed

Granting a buyer a "boilerplate" license that contains many unduly restrictive provisions

Failing to obtain appropriate indemnities

Related Legal Issues and Regulations to Watch Out For

One of the most important aspects of usage rights agreements is compliance with copyright law. As the photographer, you own the copyright to all photos you take, regardless of written agreement. Under U.S. copyright law, the copyright also includes the right to reproduce, distribute, and make derivative works based on your work. Any time someone else uses your work in a way that falls under one of those categories, they are infringing on your copyright.

This legal reality underpins the importance of a written agreement when photographers transfer the ownership of their copyright to clients. It’s also what drives the need for licensing regulations on the part of the client. For example, a licensing regulation for a magazine could include the right to use a photo in print only, within the pages of a single issue of a magazine, online publication of that issue only, and on any and all social media platforms for purposes of advertising the magazine issue.

In addition to written usage rights agreements, photographers are strongly encouraged to seek out legal advice as needed. Each state has its own laws regarding photographers’ rights and usage rights agreements. Further, photographers are not required to have a lawyer draft a usage rights agreement. However, if a photographer enters into an agreement without guidance, that photographer risks substantial losses of income, frustrating working relationships, and the potential for entering into a legally-binding agreement that they cannot afford to contest.

Practical Examples and Case Studies

Consider photography agreements by European Union based clients. In the European Union, every member state has mandatory moral rights laws that are largely the same. An upshot is that when a photographer enters into a photography agreement where the photographer (not the client) is both the creator of the photographs to be created (the work), then certain aspects of the moral rights laws may be applicable and will apply even in the United States as a result.

In a 2014 case Kendrick v. Thomson Reuters, Thomson Reuters attempted to use photographs created by journalist Kendrick without a license from Kendrick. Kendrick had tried to license his marks to Thomson Reuters in January of 2013, but Thomson Reuters refused to pay any flat license fees. For three months he continued to license to Thomson Reuters an informal oral agreement, without any formal written photography use rights agreement. Kendrick subsequently assigned his photographs to Getty Images, and as a result of that assignment, the documents were available from Getty to Thomson Reuters. Thomson Reuters proceeded to use Kendrick’s photographs without a flat fee, and as a consequence got sued for infringement. Despite Kendrick’s photographers’ rights relationship with Thomson Reuters, a federal trial court in the Eastern District of Pennyslvania, allowed Thomson Reuters to present a defense of implied license, which it allowed to be heard at trial.

The trial itself was disastrous for Kendrick, but the case was ultimately settled out of court, which means Thomson Reuters never could properly plead a fair use of the works in Kendrick or implied license, because there was no Third Party who could have validly claimed and exercised either of those defenses through Thomson Reuters on Kendrick’s behalf. Moreover , in the Kendrick case, Kendrick’s oral license was shot from being a flat fee license, which would presumably have barred Thomson Reuters from attempting to assert implied license. Those issues speak for themselves when we realize that if Kendrick had a written photography use rights agreement with Thomson Reuters, such would not have taken place.

Let’s take another real-world example of a poor photography use rights agreement. In CBP v. Government of Prince George, Maryland, Civil Action No. 8:08-cv-00160-DKC, the CBP was able to successfully establish its copyright ownership in album created by one of its employees, a police officer employed within the Prince George’s County Police Department’s Incident Management Division. Through its employment, the police officer produced a digital album which depicted a roll call of officers with their badge numbers clearly visible on their sleeves. As a result, the case was relatively easy to prove copyright infringement (among other things). You see, the police officer took the album to a graphic design shop to obtain a disc for distribution of prints. One of the employees at the graphics shop took the digital disc, made various copies and sold them to the general public.

In conditions of employment where an employee is employed in a creative role, the works may be said to be "works for hire" under the Copyright Act and employer has agency rights even over non-employees acting as agents. Although certain facts may demonstrate otherwise, the distinctions between types of employees and the ultimate question of whether a contract, under which the Plaintiff sought damages from the Defendant, was valid and enforceable, were issues to be resolved from the case.